Fenwick Tree¶

Let $f$ be some group operation (a binary associative function over a set with an identity element and inverse elements) and $A$ be an array of integers of length $N$. Denote $f$'s infix notation as $*$; that is, $f(x,y) = x*y$ for arbitrary integers $x,y$. (Since this is associative, we will omit parentheses for order of application of $f$ when using infix notation.)

The Fenwick tree is a data structure which:

- calculates the value of function $f$ in the given range $[l, r]$ (i.e. $A_l * A_{l+1} * \dots * A_r$) in $O(\log N)$ time

- updates the value of an element of $A$ in $O(\log N)$ time

- requires $O(N)$ memory (the same amount required for $A$)

- is easy to use and code, especially in the case of multidimensional arrays

The most common application of a Fenwick tree is calculating the sum of a range. For example, using addition over the set of integers as the group operation, i.e. $f(x,y) = x + y$: the binary operation, $*$, is $+$ in this case, so $A_l * A_{l+1} * \dots * A_r = A_l + A_{l+1} + \dots + A_{r}$.

The Fenwick tree is also called a Binary Indexed Tree (BIT). It was first described in a paper titled "A new data structure for cumulative frequency tables" (Peter M. Fenwick, 1994).

Description¶

Overview¶

For the sake of simplicity, we will assume that function $f$ is defined as $f(x,y) = x + y$ over the integers.

Suppose we are given an array of integers, $A[0 \dots N-1]$. (Note that we are using zero-based indexing.) A Fenwick tree is just an array, $T[0 \dots N-1]$, where each element is equal to the sum of elements of $A$ in some range, $[g(i), i]$:

where $g$ is some function that satisfies $0 \le g(i) \le i$. We will define $g$ in the next few paragraphs.

The data structure is called a tree because there is a nice representation of it in the form of a tree, although we don't need to model an actual tree with nodes and edges. We only need to maintain the array $T$ to handle all queries.

Note: The Fenwick tree presented here uses zero-based indexing. Many people use a version of the Fenwick tree that uses one-based indexing. As such, you will also find an alternative implementation which uses one-based indexing in the implementation section. Both versions are equivalent in terms of time and memory complexity.

Now we can write some pseudo-code for the two operations mentioned above. Below, we get the sum of elements of $A$ in the range $[0, r]$ and update (increase) some element $A_i$:

def sum(int r):

res = 0

while (r >= 0):

res += t[r]

r = g(r) - 1

return res

def increase(int i, int delta):

for all j with g(j) <= i <= j:

t[j] += delta

The function sum works as follows:

- First, it adds the sum of the range $[g(r), r]$ (i.e. $T[r]$) to the

result. - Then, it "jumps" to the range $[g(g(r)-1), g(r)-1]$ and adds this range's sum to the

result. - This continues until it "jumps" from $[0, g(g( \dots g(r)-1 \dots -1)-1)]$ to $[g(-1), -1]$; this is where the

sumfunction stops jumping.

The function increase works with the same analogy, but it "jumps" in the direction of increasing indices:

- The sum for each range of the form $[g(j), j]$ which satisfies the condition $g(j) \le i \le j$ is increased by

delta; that is,t[j] += delta. Therefore, it updates all elements in $T$ that correspond to ranges in which $A_i$ lies.

The complexity of both sum and increase depend on the function $g$.

There are many ways to choose the function $g$ such that $0 \le g(i) \le i$ for all $i$.

For instance, the function $g(i) = i$ works, which yields $T = A$ (in which case, the summation queries are slow).

We could also take the function $g(i) = 0$.

This would correspond to prefix sum arrays (in which case, finding the sum of the range $[0, i]$ will only take constant time; however, updates are slow).

The clever part of the algorithm for Fenwick trees is how it uses a special definition of the function $g$ which can handle both operations in $O(\log N)$ time.

Definition of $g(i)$¶

The computation of $g(i)$ is defined using the following simple operation: we replace all trailing $1$ bits in the binary representation of $i$ with $0$ bits.

In other words, if the least significant digit of $i$ in binary is $0$, then $g(i) = i$. And otherwise the least significant digit is a $1$, and we take this $1$ and all other trailing $1$s and flip them.

For instance we get

There exists a simple implementation using bitwise operations for the non-trivial operation described above:

where $\&$ is the bitwise AND operator. It is not hard to convince yourself that this solution does the same thing as the operation described above.

Now, we just need to find a way to iterate over all $j$'s, such that $g(j) \le i \le j$.

It is easy to see that we can find all such $j$'s by starting with $i$ and flipping the last unset bit. We will call this operation $h(j)$. For example, for $i = 10$ we have:

Unsurprisingly, there also exists a simple way to perform $h$ using bitwise operations:

where $|$ is the bitwise OR operator.

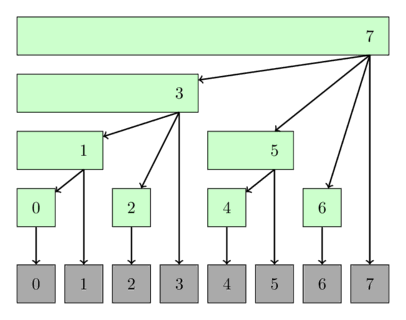

The following image shows a possible interpretation of the Fenwick tree as tree. The nodes of the tree show the ranges they cover.

Implementation¶

Finding sum in one-dimensional array¶

Here we present an implementation of the Fenwick tree for sum queries and single updates.

The normal Fenwick tree can only answer sum queries of the type $[0, r]$ using sum(int r), however we can also answer other queries of the type $[l, r]$ by computing two sums $[0, r]$ and $[0, l-1]$ and subtract them.

This is handled in the sum(int l, int r) method.

Also this implementation supports two constructors. You can create a Fenwick tree initialized with zeros, or you can convert an existing array into the Fenwick form.

struct FenwickTree {

vector<int> bit; // binary indexed tree

int n;

FenwickTree(int n) {

this->n = n;

bit.assign(n, 0);

}

FenwickTree(vector<int> const &a) : FenwickTree(a.size()) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < a.size(); i++)

add(i, a[i]);

}

int sum(int r) {

int ret = 0;

for (; r >= 0; r = (r & (r + 1)) - 1)

ret += bit[r];

return ret;

}

int sum(int l, int r) {

return sum(r) - sum(l - 1);

}

void add(int idx, int delta) {

for (; idx < n; idx = idx | (idx + 1))

bit[idx] += delta;

}

};

Linear construction¶

The above implementation requires $O(N \log N)$ time. It's possible to improve that to $O(N)$ time.

The idea is, that the number $a[i]$ at index $i$ will contribute to the range stored in $bit[i]$, and to all ranges that the index $i | (i + 1)$ contributes to. So by adding the numbers in order, you only have to push the current sum further to the next range, where it will then get pushed further to the next range, and so on.

FenwickTree(vector<int> const &a) : FenwickTree(a.size()){

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

bit[i] += a[i];

int r = i | (i + 1);

if (r < n) bit[r] += bit[i];

}

}

Finding minimum of $[0, r]$ in one-dimensional array¶

It is obvious that there is no easy way of finding minimum of range $[l, r]$ using Fenwick tree, as Fenwick tree can only answer queries of type $[0, r]$.

Additionally, each time a value is update'd, the new value has to be smaller than the current value.

Both significant limitations are because the $min$ operation together with the set of integers doesn't form a group, as there are no inverse elements.

struct FenwickTreeMin {

vector<int> bit;

int n;

const int INF = (int)1e9;

FenwickTreeMin(int n) {

this->n = n;

bit.assign(n, INF);

}

FenwickTreeMin(vector<int> a) : FenwickTreeMin(a.size()) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < a.size(); i++)

update(i, a[i]);

}

int getmin(int r) {

int ret = INF;

for (; r >= 0; r = (r & (r + 1)) - 1)

ret = min(ret, bit[r]);

return ret;

}

void update(int idx, int val) {

for (; idx < n; idx = idx | (idx + 1))

bit[idx] = min(bit[idx], val);

}

};

Note: it is possible to implement a Fenwick tree that can handle arbitrary minimum range queries and arbitrary updates. The paper Efficient Range Minimum Queries using Binary Indexed Trees describes such an approach. However with that approach you need to maintain a second binary indexed tree over the data, with a slightly different structure, since one tree is not enough to store the values of all elements in the array. The implementation is also a lot harder compared to the normal implementation for sums.

Finding sum in two-dimensional array¶

As claimed before, it is very easy to implement Fenwick Tree for multidimensional array.

struct FenwickTree2D {

vector<vector<int>> bit;

int n, m;

// init(...) { ... }

int sum(int x, int y) {

int ret = 0;

for (int i = x; i >= 0; i = (i & (i + 1)) - 1)

for (int j = y; j >= 0; j = (j & (j + 1)) - 1)

ret += bit[i][j];

return ret;

}

void add(int x, int y, int delta) {

for (int i = x; i < n; i = i | (i + 1))

for (int j = y; j < m; j = j | (j + 1))

bit[i][j] += delta;

}

};

One-based indexing approach¶

For this approach we change the requirements and definition for $T[]$ and $g()$ a little bit. We want $T[i]$ to store the sum of $[g(i)+1; i]$. This changes the implementation a little bit, and allows for a similar nice definition for $g(i)$:

def sum(int r):

res = 0

while (r > 0):

res += t[r]

r = g(r)

return res

def increase(int i, int delta):

for all j with g(j) < i <= j:

t[j] += delta

The computation of $g(i)$ is defined as: toggling of the last set $1$ bit in the binary representation of $i$.

The last set bit can be extracted using $i ~\&~ (-i)$, so the operation can be expressed as:

And it's not hard to see, that you need to change all values $T[j]$ in the sequence $i,~ h(i),~ h(h(i)),~ \dots$ when you want to update $A[j]$, where $h(i)$ is defined as:

As you can see, the main benefit of this approach is that the binary operations complement each other very nicely.

The following implementation can be used like the other implementations, however it uses one-based indexing internally.

struct FenwickTreeOneBasedIndexing {

vector<int> bit; // binary indexed tree

int n;

FenwickTreeOneBasedIndexing(int n) {

this->n = n + 1;

bit.assign(n + 1, 0);

}

FenwickTreeOneBasedIndexing(vector<int> a)

: FenwickTreeOneBasedIndexing(a.size()) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < a.size(); i++)

add(i, a[i]);

}

int sum(int idx) {

int ret = 0;

for (++idx; idx > 0; idx -= idx & -idx)

ret += bit[idx];

return ret;

}

int sum(int l, int r) {

return sum(r) - sum(l - 1);

}

void add(int idx, int delta) {

for (++idx; idx < n; idx += idx & -idx)

bit[idx] += delta;

}

};

Range operations¶

A Fenwick tree can support the following range operations:

- Point Update and Range Query

- Range Update and Point Query

- Range Update and Range Query

1. Point Update and Range Query¶

This is just the ordinary Fenwick tree as explained above.

2. Range Update and Point Query¶

Using simple tricks we can also do the reverse operations: increasing ranges and querying for single values.

Let the Fenwick tree be initialized with zeros.

Suppose that we want to increment the interval $[l, r]$ by $x$.

We make two point update operations on Fenwick tree which are add(l, x) and add(r+1, -x).

If we want to get the value of $A[i]$, we just need to take the prefix sum using the ordinary range sum method. To see why this is true, we can just focus on the previous increment operation again. If $i < l$, then the two update operations have no effect on the query and we get the sum $0$. If $i \in [l, r]$, then we get the answer $x$ because of the first update operation. And if $i > r$, then the second update operation will cancel the effect of first one.

The following implementation uses one-based indexing.

void add(int idx, int val) {

for (++idx; idx < n; idx += idx & -idx)

bit[idx] += val;

}

void range_add(int l, int r, int val) {

add(l, val);

add(r + 1, -val);

}

int point_query(int idx) {

int ret = 0;

for (++idx; idx > 0; idx -= idx & -idx)

ret += bit[idx];

return ret;

}

Note: of course it is also possible to increase a single point $A[i]$ with range_add(i, i, val).

3. Range Update and Range Query¶

To support both range updates and range queries we will use two BITs namely $B_1[]$ and $B_2[]$, initialized with zeros.

Suppose that we want to increment the interval $[l, r]$ by the value $x$.

Similarly as in the previous method, we perform two point updates on $B_1$: add(B1, l, x) and add(B1, r+1, -x).

And we also update $B_2$. The details will be explained later.

def range_add(l, r, x):

add(B1, l, x)

add(B1, r+1, -x)

add(B2, l, x*(l-1))

add(B2, r+1, -x*r))

We can write the range sum as difference of two terms, where we use $B_1$ for first term and $B_2$ for second term. The difference of the queries will give us prefix sum over $[0, i]$.

The last expression is exactly equal to the required terms. Thus we can use $B_2$ for shaving off extra terms when we multiply $B_1[i]\times i$.

We can find arbitrary range sums by computing the prefix sums for $l-1$ and $r$ and taking the difference of them again.

def add(b, idx, x):

while idx <= N:

b[idx] += x

idx += idx & -idx

def range_add(l,r,x):

add(B1, l, x)

add(B1, r+1, -x)

add(B2, l, x*(l-1))

add(B2, r+1, -x*r)

def sum(b, idx):

total = 0

while idx > 0:

total += b[idx]

idx -= idx & -idx

return total

def prefix_sum(idx):

return sum(B1, idx)*idx - sum(B2, idx)

def range_sum(l, r):

return prefix_sum(r) - prefix_sum(l-1)

Practice Problems¶

- UVA 12086 - Potentiometers

- LOJ 1112 - Curious Robin Hood

- LOJ 1266 - Points in Rectangle

- Codechef - SPREAD

- SPOJ - CTRICK

- SPOJ - MATSUM

- SPOJ - DQUERY

- SPOJ - NKTEAM

- SPOJ - YODANESS

- SRM 310 - FloatingMedian

- SPOJ - Ada and Behives

- Hackerearth - Counting in Byteland

- DevSkill - Shan and String (archived)

- Codeforces - Little Artem and Time Machine

- Codeforces - Hanoi Factory

- SPOJ - Tulip and Numbers

- SPOJ - SUMSUM

- SPOJ - Sabir and Gifts

- SPOJ - The Permutation Game Again

- SPOJ - Zig when you Zag

- SPOJ - Cryon

- SPOJ - Weird Points

- SPOJ - Its a Murder

- SPOJ - Bored of Suffixes and Prefixes

- SPOJ - Mega Inversions

- Codeforces - Subsequences

- Codeforces - Ball

- GYM - The Kamphaeng Phet's Chedis

- Codeforces - Garlands

- Codeforces - Inversions after Shuffle

- GYM - Cairo Market

- Codeforces - Goodbye Souvenir

- SPOJ - Ada and Species

- Codeforces - Thor

- CSES - Forest Queries II

- Latin American Regionals 2017 - Fundraising