Finding the nearest pair of points¶

Problem statement¶

Given $n$ points on the plane. Each point $p_i$ is defined by its coordinates $(x_i,y_i)$. It is required to find among them two such points, such that the distance between them is minimal:

We take the usual Euclidean distances:

The trivial algorithm - iterating over all pairs and calculating the distance for each — works in $O(n^2)$.

The algorithm running in time $O(n \log n)$ is described below. This algorithm was proposed by Shamos and Hoey in 1975. (Source: Ch. 5 Notes of Algorithm Design by Kleinberg & Tardos, also see here) Preparata and Shamos also showed that this algorithm is optimal in the decision tree model.

Algorithm¶

We construct an algorithm according to the general scheme of divide-and-conquer algorithms: the algorithm is designed as a recursive function, to which we pass a set of points; this recursive function splits this set in half, calls itself recursively on each half, and then performs some operations to combine the answers. The operation of combining consist of detecting the cases when one point of the optimal solution fell into one half, and the other point into the other (in this case, recursive calls from each of the halves cannot detect this pair separately). The main difficulty, as always in case of divide and conquer algorithms, lies in the effective implementation of the merging stage. If a set of $n$ points is passed to the recursive function, then the merge stage should work no more than $O(n)$, then the asymptotics of the whole algorithm $T(n)$ will be found from the equation:

The solution to this equation, as is known, is $T(n) = O(n \log n).$

So, we proceed on to the construction of the algorithm. In order to come to an effective implementation of the merge stage in the future, we will divide the set of points into two subsets, according to their $x$-coordinates: In fact, we draw some vertical line dividing the set of points into two subsets of approximately the same size. It is convenient to make such a partition as follows: We sort the points in the standard way as pairs of numbers, ie.:

Then take the middle point after sorting $p_m (m = \lfloor n/2 \rfloor)$, and all the points before it and the $p_m$ itself are assigned to the first half, and all the points after it - to the second half:

Now, calling recursively on each of the sets $A_1$ and $A_2$, we will find the answers $h_1$ and $h_2$ for each of the halves. And take the best of them: $h = \min(h_1, h_2)$.

Now we need to make a merge stage, i.e. we try to find such pairs of points, for which the distance between which is less than $h$ and one point is lying in $A_1$ and the other in $A_2$. It is obvious that it is sufficient to consider only those points that are separated from the vertical line by a distance less than $h$, i.e. the set $B$ of the points considered at this stage is equal to:

For each point in the set $B$, we try to find the points that are closer to it than $h$. For example, it is sufficient to consider only those points whose $y$-coordinate differs by no more than $h$. Moreover, it makes no sense to consider those points whose $y$-coordinate is greater than the $y$-coordinate of the current point. Thus, for each point $p_i$ we define the set of considered points $C(p_i)$ as follows:

If we sort the points of the set $B$ by $y$-coordinate, it will be very easy to find $C(p_i)$: these are several points in a row ahead to the point $p_i$.

So, in the new notation, the merging stage looks like this: build a set $B$, sort the points in it by $y$-coordinate, then for each point $p_i \in B$ consider all points $p_j \in C(p_i)$, and for each pair $(p_i,p_j)$ calculate the distance and compare with the current best distance.

At first glance, this is still a non-optimal algorithm: it seems that the sizes of sets $C(p_i)$ will be of order $n$, and the required asymptotics will not work. However, surprisingly, it can be proved that the size of each of the sets $C(p_i)$ is a quantity $O(1)$, i.e. it does not exceed some small constant regardless of the points themselves. Proof of this fact is given in the next section.

Finally, we pay attention to the sorting, which the above algorithm contains: first,sorting by pairs $(x, y)$, and then second, sorting the elements of the set $B$ by $y$. In fact, both of these sorts inside the recursive function can be eliminated (otherwise we would not reach the $O(n)$ estimate for the merging stage, and the general asymptotics of the algorithm would be $O(n \log^2 n)$). It is easy to get rid of the first sort — it is enough to perform this sort before starting the recursion: after all, the elements themselves do not change inside the recursion, so there is no need to sort again. With the second sorting a little more difficult to perform, performing it previously will not work. But, remembering the merge sort, which also works on the principle of divide-and-conquer, we can simply embed this sort in our recursion. Let recursion, taking some set of points (as we remember,ordered by pairs $(x, y)$), return the same set, but sorted by the $y$-coordinate. To do this, simply merge (in $O(n)$) the two results returned by recursive calls. This will result in a set sorted by $y$-coordinate.

Evaluation of the asymptotics¶

To show that the above algorithm is actually executed in $O(n \log n)$, we need to prove the following fact: $|C(p_i)| = O(1)$.

So, let us consider some point $p_i$; recall that the set $C(p_i)$ is a set of points whose $y$-coordinate lies in the segment $[y_i-h; y_i]$, and, moreover, along the $x$ coordinate, the point $p_i$ itself, and all the points of the set $C(p_i)$ lie in the band width $2h$. In other words, the points we are considering $p_i$ and $C(p_i)$ lie in a rectangle of size $2h \times h$.

Our task is to estimate the maximum number of points that can lie in this rectangle $2h \times h$; thus, we estimate the maximum size of the set $C(p_i)$. At the same time, when evaluating, we must not forget that there may be repeated points.

Remember that $h$ was obtained from the results of two recursive calls — on sets $A_1$ and $A_2$, and $A_1$ contains points to the left of the partition line and partially on it, $A_2$ contains the remaining points of the partition line and points to the right of it. For any pair of points from $A_1$, as well as from $A_2$, the distance can not be less than $h$ — otherwise it would mean incorrect operation of the recursive function.

To estimate the maximum number of points in the rectangle $2h \times h$ we divide it into two squares $h \times h$, the first square include all points $C(p_i) \cap A_1$, and the second contains all the others, i.e. $C(p_i) \cap A_2$. It follows from the above considerations that in each of these squares the distance between any two points is at least $h$.

We show that there are at most four points in each square. For example, this can be done as follows: divide the square into $4$ sub-squares with sides $h/2$. Then there can be no more than one point in each of these sub-squares (since even the diagonal is equal to $h / \sqrt{2}$, which is less than $h$). Therefore, there can be no more than $4$ points in the whole square.

So, we have proved that in a rectangle $2h \times h$ can not be more than $4 \cdot 2 = 8$ points, and, therefore, the size of the set $C(p_i)$ cannot exceed $7$, as required.

Implementation¶

We introduce a data structure to store a point (its coordinates and a number) and comparison operators required for two types of sorting:

struct pt {

int x, y, id;

};

struct cmp_x {

bool operator()(const pt & a, const pt & b) const {

return a.x < b.x || (a.x == b.x && a.y < b.y);

}

};

struct cmp_y {

bool operator()(const pt & a, const pt & b) const {

return a.y < b.y;

}

};

int n;

vector<pt> a;

For a convenient implementation of recursion, we introduce an auxiliary function upd_ans(), which will calculate the distance between two points and check whether it is better than the current answer:

double mindist;

pair<int, int> best_pair;

void upd_ans(const pt & a, const pt & b) {

double dist = sqrt((a.x - b.x)*(a.x - b.x) + (a.y - b.y)*(a.y - b.y));

if (dist < mindist) {

mindist = dist;

best_pair = {a.id, b.id};

}

}

Finally, the implementation of the recursion itself. It is assumed that before calling it, the array $a[]$ is already sorted by $x$-coordinate. In recursion we pass just two pointers $l, r$, which indicate that it should look for the answer for $a[l \ldots r)$. If the distance between $r$ and $l$ is too small, the recursion must be stopped, and perform a trivial algorithm to find the nearest pair and then sort the subarray by $y$-coordinate.

To merge two sets of points received from recursive calls into one (ordered by $y$-coordinate), we use the standard STL $merge()$ function, and create an auxiliary buffer $t[]$(one for all recursive calls). (Using inplace_merge () is impractical because it generally does not work in linear time.)

Finally, the set $B$ is stored in the same array $t$.

vector<pt> t;

void rec(int l, int r) {

if (r - l <= 3) {

for (int i = l; i < r; ++i) {

for (int j = i + 1; j < r; ++j) {

upd_ans(a[i], a[j]);

}

}

sort(a.begin() + l, a.begin() + r, cmp_y());

return;

}

int m = (l + r) >> 1;

int midx = a[m].x;

rec(l, m);

rec(m, r);

merge(a.begin() + l, a.begin() + m, a.begin() + m, a.begin() + r, t.begin(), cmp_y());

copy(t.begin(), t.begin() + r - l, a.begin() + l);

int tsz = 0;

for (int i = l; i < r; ++i) {

if (abs(a[i].x - midx) < mindist) {

for (int j = tsz - 1; j >= 0 && a[i].y - t[j].y < mindist; --j)

upd_ans(a[i], t[j]);

t[tsz++] = a[i];

}

}

}

By the way, if all the coordinates are integer, then at the time of the recursion you can not move to fractional values, and store in $mindist$ the square of the minimum distance.

In the main program, recursion should be called as follows:

t.resize(n);

sort(a.begin(), a.end(), cmp_x());

mindist = 1E20;

rec(0, n);

Linear time randomized algorithms¶

A randomized algorithm with linear expected time¶

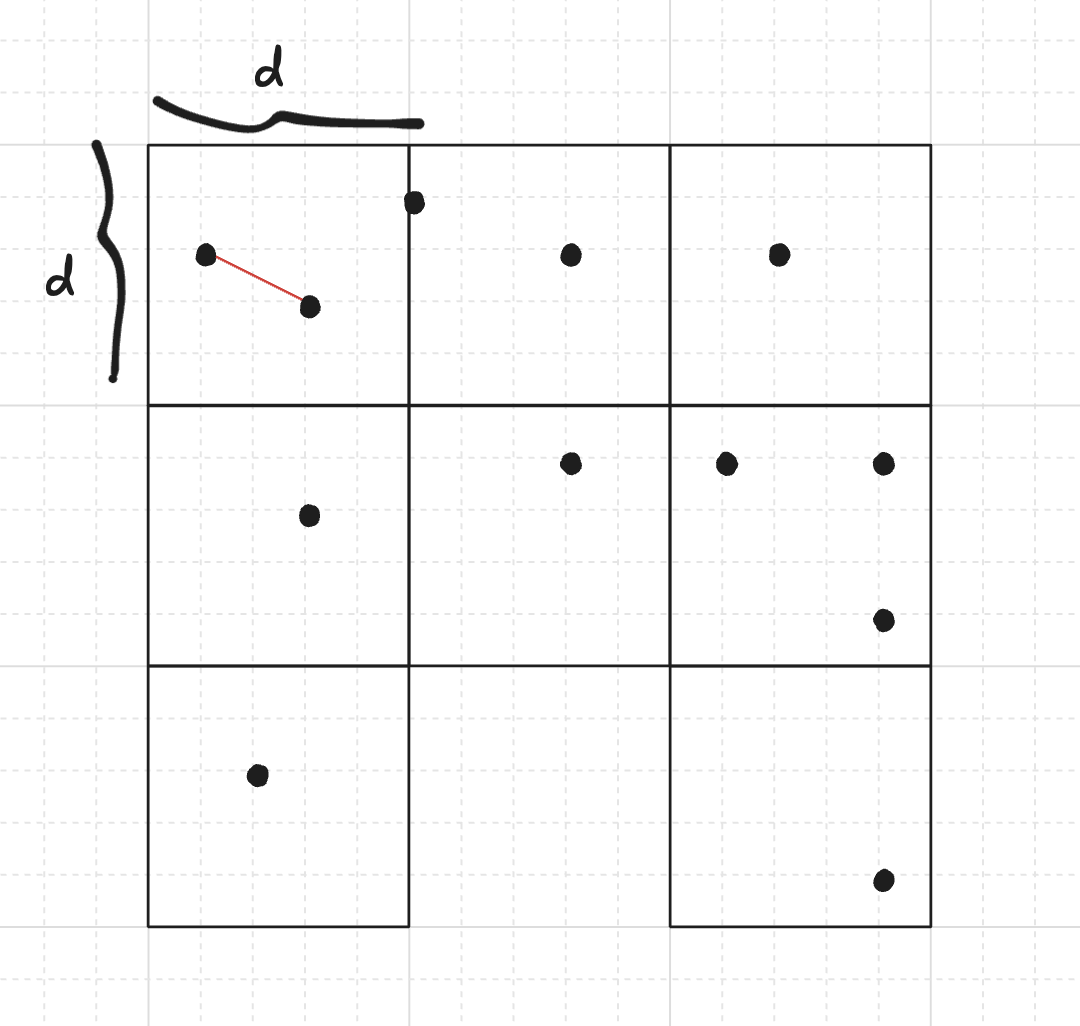

An alternative method, originally proposed by Rabin in 1976, arises from a very simple idea to heuristically improve the runtime: We can divide the plane into a grid of $d \times d$ squares, then it is only required to test distances between same-block or adjacent-block points (unless all squares are disconnected from each other, but we will avoid this by design), since any other pair has a larger distance than the two points in the same square.

We will consider only the squares containing at least one point. Denote by $n_1, n_2, \dots, n_k$ the number of points in each of the $k$ remaining squares. Assuming at least two points are in the same or in adjacent squares, and that there are no duplicated points, the time complexity is $\Theta\!\left(\sum\limits_{i=1}^k n_i^2\right)$. We can look for duplicated points in expected linear time using a hash table, and in the affirmative case, the answer is this pair.

Proof

For the $i$-th square containing $n_i$ points, the number of pairs inside is $\Theta(n_i^2)$. If the $i$-th square is adjacent to the $j$-th square, then we also perform $n_i n_j \le \max(n_i, n_j)^2 \le n_i^2 + n_j^2$ distance comparisons. Notice that each square has at most $8$ adjacent squares, so we can bound the sum of all comparisons by $\Theta(\sum_{i=1}^{k} n_i^2)$. $\quad \blacksquare$

Now we need to decide on how to set $d$ so that it minimizes $\Theta\!\left(\sum\limits_{i=1}^k n_i^2\right)$.

Choosing d¶

We need $d$ to be an approximation of the minimum distance $d$. Richard Lipton proposed to sample $n$ distances randomly and choose $d$ to be the smallest of these distances as an approximation for $d$. We now prove that the expected running time of the algorithm is linear.

Proof

Imagine the disposition of points in squares with a particular choice of $d$, say $x$. Consider $d$ a random variable, resulting from our sampling of distances. Let's define $C(x) := \sum_{i=1}^{k(x)} n_i(x)^2$ as the cost estimation for a particular disposition when we choose $d=x$. Now, let's define $\lambda(x)$ such that $C(x) = \lambda(x) \, n$. What is the probability that such choice $x$ survives the sampling of $n$ independent distances? If a single pair among the sampled ones has distance smaller than $x$, this arrangement will be replaced by the smaller $d$. Inside a square, about $1/16$ of the pairs would raise a smaller distance (imagine four subsquares in every square; using the pigeonhole principle, at least one subsquare has $n_i/4$ points), so we have about $\sum_{i=1}^{k} {n_i/4 \choose 2} \approx \sum_{i=1}^{k} \frac{1}{16} {n_i \choose 2}$ pairs which yield a smaller final $d$. This is, approximately, $\frac{1}{32} \sum_{i=1}^{k} n_i^2 = \frac{1}{32} \lambda(x) n$. On the other hand, there are about $\frac{1}{2} n^2$ pairs that can be sampled. We have that the probability of sampling a pair with distance smaller than $x$ is at least (approximately)

so the probability of at least one such pair being chosen during the $n$ rounds (and therefore finding a smaller $d$) is

(we have used that $(1 + x)^n \le e^{xn}$ for any real number $x$, check Bernoulli inequalities).

Notice this goes to $1$ exponentially as $\lambda(x)$ increases. This hints that $\lambda$ will be small for a poorly chosen $d$.

We have shown that $\Pr(d \le x) \ge 1 - e^{-\lambda(x)/16}$, or equivalently, $\Pr(d \ge x) \le e^{-\lambda(x)/16}$. We need to know $\Pr(\lambda(d) \ge \text{something})$ to be able to estimate its expected value. We notice that $\lambda(d) \ge \lambda(x) \iff d \ge x$. This is because making the squares smaller only reduces the number of points in each square (splits the points into other squares), and this keeps reducing the sum of squares. Therefore,

(we have used that $E[X] = \int_0^{+\infty} \Pr(X \ge x) \, \mathrm{d}x$, check Stackexchange proof).

Finally, $\mathbb{E}[C(d)] = \mathbb{E}[\lambda(d) \, n] \le 16n$, and the expected running time is $O(n)$, with a reasonable constant factor. $\quad \blacksquare$

Implementation of the algorithm¶

The advantage of this algorithm is that it is straightforward to implement, but still has good performance in practise. We first sample $n$ distances and set $d$ as the minimum of the distances. Then we insert points into the "blocks" by using a hash table from 2D coordinates to a vector of points. Finally, just compute distances between same-block pairs and adjacent-block pairs. Hash table operations have $O(1)$ expected time cost, and therefore our algorithm retains the $O(n)$ expected time cost with an increased constant.

Check out this submission to Library Checker.

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

using ll = long long;

using ld = long double;

struct pt {

ll x, y;

pt() {}

pt(ll x_, ll y_) : x(x_), y(y_) {}

void read() {

cin >> x >> y;

}

};

bool operator==(const pt& a, const pt& b) {

return a.x == b.x and a.y == b.y;

}

struct CustomHashPoint {

size_t operator()(const pt& p) const {

static const uint64_t C = chrono::steady_clock::now().time_since_epoch().count();

return C ^ ((p.x << 32) ^ p.y);

}

};

ll dist2(pt a, pt b) {

ll dx = a.x - b.x;

ll dy = a.y - b.y;

return dx*dx + dy*dy;

}

pair<int,int> closest_pair_of_points(vector<pt> P) {

int n = int(P.size());

assert(n >= 2);

// if there is a duplicated point, we have the solution

unordered_map<pt,int,CustomHashPoint> previous;

for (int i = 0; i < int(P.size()); ++i) {

auto it = previous.find(P[i]);

if (it != previous.end()) {

return {it->second, i};

}

previous[P[i]] = i;

}

unordered_map<pt,vector<int>,CustomHashPoint> grid;

grid.reserve(n);

mt19937 rd(chrono::system_clock::now().time_since_epoch().count());

uniform_int_distribution<int> dis(0, n-1);

ll d2 = dist2(P[0], P[1]);

pair<int,int> closest = {0, 1};

auto candidate_closest = [&](int i, int j) -> void {

ll ab2 = dist2(P[i], P[j]);

if (ab2 < d2) {

d2 = ab2;

closest = {i, j};

}

};

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

int j = dis(rd);

int k = dis(rd);

while (j == k) k = dis(rd);

candidate_closest(j, k);

}

ll d = ll( sqrt(ld(d2)) + 1 );

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

grid[{P[i].x/d, P[i].y/d}].push_back(i);

}

// same block

for (const auto& it : grid) {

int k = int(it.second.size());

for (int i = 0; i < k; ++i) {

for (int j = i+1; j < k; ++j) {

candidate_closest(it.second[i], it.second[j]);

}

}

}

// adjacent blocks

for (const auto& it : grid) {

auto coord = it.first;

for (int dx = 0; dx <= 1; ++dx) {

for (int dy = -1; dy <= 1; ++dy) {

if (dx == 0 and dy == 0) continue;

pt neighbour = pt(

coord.x + dx,

coord.y + dy

);

for (int i : it.second) {

if (not grid.count(neighbour)) continue;

for (int j : grid.at(neighbour)) {

candidate_closest(i, j);

}

}

}

}

}

return closest;

}

An alternative randomized linear expected time algorithm¶

Now we introduce a different randomized algorithm which is less practical but very easy to show that it runs in expected linear time.

- Permute the $n$ points randomly

- Take $\delta := \operatorname{dist}(p_1, p_2)$

- Partition the plane in squares of side $\delta/2$

- For $i = 1,2,\dots,n$:

- Take the square corresponding to $p_i$

- Iterate over the $25$ squares within two steps to our square in the grid of squares partitioning the plane

- If some $p_j$ in those squares has $\operatorname{dist}(p_j, p_i) < \delta$, then

- Recompute the partition and squares with $\delta := \operatorname{dist}(p_j, p_i)$

- Store points $p_1, \dots, p_i$ in the corresponding squares

- else, store $p_i$ in the corresponding square

- output $\delta$

The correctness follows from the fact that at any moment we already have some pair with distance $\delta$, so we try to find only new pairs with distance smaller than $\delta$. Since each square has side $\delta/2$, a candidate pair can be at most at a distance of $2$ squares, so for a given point we check candidates in the surrounding $25$ squares. Any point in a square further away will always give a distace larger than $\delta$.

While this algorithm may look slow, because of recomputing everything multiple times, we can show the total expected cost is linear.

Proof

Let $X_i$ the random variable that is $1$ when point $p_i$ causes a change of $\delta$ and a recomputation of the data structures, and $0$ if not. It is easy to show that the cost is $O(n + \sum_{i=1}^{n} i X_i)$, since on the $i$-th step we are considering only the first $i$ points. However, turns out that $\Pr(X_i = 1) \le \frac{2}{i}$. This is because on the $i$-th step, $\delta$ is the distance of the closest pair in $\{p_1,\dots,p_i\}$, and $\Pr(X_i = 1)$ is the probability of $p_i$ belonging to the closest pair, which only happens in $2(i-1)$ pairs out of the $i(i-1)$ possible pairs (assuming all distances are different), so the probability is at most $\frac{2(i-1)}{i(i-1)} = \frac{2}{i}$, since we previously shuffled the points uniformly.

We can therefore see that the expected cost is

Generalization: finding a triangle with minimal perimeter¶

The algorithm described above is interestingly generalized to this problem: among a given set of points, choose three different points so that the sum of pairwise distances between them is the smallest.

In fact, to solve this problem, the algorithm remains the same: we divide the field into two halves of the vertical line, call the solution recursively on both halves, choose the minimum $minper$ from the found perimeters, build a strip with the thickness of $minper / 2$, and iterate through all triangles that can improve the answer. (Note that the triangle with perimeter $\le minper$ has the longest side $\le minper / 2$.)

Practice problems¶

- UVA 10245 "The Closest Pair Problem" [difficulty: low]

- SPOJ #8725 CLOPPAIR "Closest Point Pair" [difficulty: low]

- CODEFORCES Team Olympiad Saratov - 2011 "Minimum amount" [difficulty: medium]

- Google CodeJam 2009 Final "Min Perimeter" [difficulty: medium]

- SPOJ #7029 CLOSEST "Closest Triple" [difficulty: medium]

- TIMUS 1514 National Park [difficulty: medium]