Newton's method for finding roots¶

This is an iterative method invented by Isaac Newton around 1664. However, this method is also sometimes called the Raphson method, since Raphson invented the same algorithm a few years after Newton, but his article was published much earlier.

The task is as follows. Given the following equation:

We want to solve the equation. More precisely, we want to find one of its roots (it is assumed that the root exists). It is assumed that $f(x)$ is continuous and differentiable on an interval $[a, b]$.

Algorithm¶

The input parameters of the algorithm consist of not only the function $f(x)$ but also the initial approximation - some $x_0$, with which the algorithm starts.

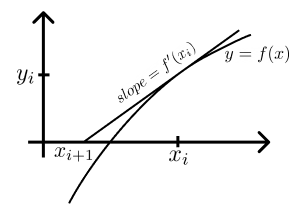

Suppose we have already calculated $x_i$, calculate $x_{i+1}$ as follows. Draw the tangent to the graph of the function $f(x)$ at the point $x = x_i$, and find the point of intersection of this tangent with the $x$-axis. $x_{i+1}$ is set equal to the $x$-coordinate of the point found, and we repeat the whole process from the beginning.

It is not difficult to obtain the following formula,

First, we calculate the slope $f'(x)$, derivative of $f(x)$, and then determine the equation of the tangent which is,

The tangent intersects with the x-axis at cordinate, $y = 0$ and $x = x_{i+1}$,

Now, solving the equation we get the value of $x_{i+1}$.

It is intuitively clear that if the function $f(x)$ is "good" (smooth), and $x_i$ is close enough to the root, then $x_{i+1}$ will be even closer to the desired root.

The rate of convergence is quadratic, which, conditionally speaking, means that the number of exact digits in the approximate value $x_i$ doubles with each iteration.

Application for calculating the square root¶

Let's use the calculation of square root as an example of Newton's method.

If we substitute $f(x) = x^2 - n$, then after simplifying the expression, we get:

The first typical variant of the problem is when a rational number $n$ is given, and its root must be calculated with some accuracy eps:

double sqrt_newton(double n) {

const double eps = 1E-15;

double x = 1;

for (;;) {

double nx = (x + n / x) / 2;

if (abs(x - nx) < eps)

break;

x = nx;

}

return x;

}

Another common variant of the problem is when we need to calculate the integer root (for the given $n$ find the largest $x$ such that $x^2 \le n$). Here it is necessary to slightly change the termination condition of the algorithm, since it may happen that $x$ will start to "jump" near the answer. Therefore, we add a condition that if the value $x$ has decreased in the previous step, and it tries to increase at the current step, then the algorithm must be stopped.

int isqrt_newton(int n) {

int x = 1;

bool decreased = false;

for (;;) {

int nx = (x + n / x) >> 1;

if (x == nx || nx > x && decreased)

break;

decreased = nx < x;

x = nx;

}

return x;

}

Finally, we are given the third variant - for the case of bignum arithmetic. Since the number $n$ can be large enough, it makes sense to pay attention to the initial approximation. Obviously, the closer it is to the root, the faster the result will be achieved. It is simple enough and effective to take the initial approximation as the number $2^{\textrm{bits}/2}$, where $\textrm{bits}$ is the number of bits in the number $n$. Here is the Java code that demonstrates this variant:

public static BigInteger isqrtNewton(BigInteger n) {

BigInteger a = BigInteger.ONE.shiftLeft(n.bitLength() / 2);

boolean p_dec = false;

for (;;) {

BigInteger b = n.divide(a).add(a).shiftRight(1);

if (a.compareTo(b) == 0 || a.compareTo(b) < 0 && p_dec)

break;

p_dec = a.compareTo(b) > 0;

a = b;

}

return a;

}

For example, this code is executed in $60$ milliseconds for $n = 10^{1000}$, and if we remove the improved selection of the initial approximation (just starting with $1$), then it will be executed in about $120$ milliseconds.